A new SAG mill at PT Freeport Indonesia is replacing the power of gravity to turn big rocks into little rocks and maintain optimum production in the underground era.

A new SAG mill at PT Freeport Indonesia is replacing the power of gravity to turn big rocks into little rocks and maintain optimum production in the underground era.

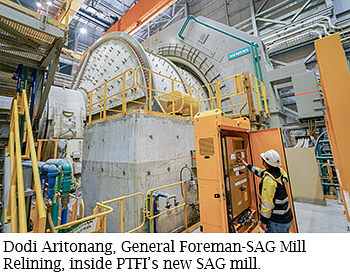

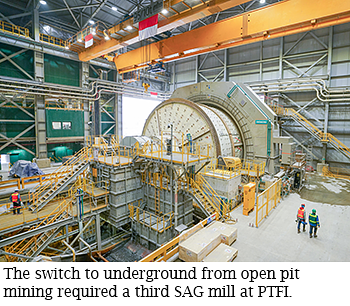

The newest semi-autogenous grinding (SAG) mill went into operation in December. It is one of several new facilities required for PTFI to process at a mine-mill optimal rate of 240,000 metric tons of ore per day. This mill rate, along with the mine ore grade and copper mineralogy, produces 3 million metric tons of copper concentrate annually, which drove the design capacity for the new Manyar smelter complex under construction in Gresik, East Java, Indonesia.

The combination of the new Manyar smelter along with the expansion of the preexisting Gresik smelter will provide the 3 million tons per year of in-country capacity to match the optimal mine-mill production. A video showing much of the new equipment at PTFI, including SAG 3, is available here.

The need for a new SAG mill was recognized long before 2019 when the Grasberg open pit was completed and 100 percent of the ore at PTFI would be from underground mines (Grasberg Block Cave, Deep MLZ mine and Big Gossan), said George Banini, Executive Vice President-Operations.

The Grasberg pit was near the top of the mountain range. Its ore flow system was at an elevation of over 11,000 feet while the mill level is at 9,000 feet. This required a unique solution to get the ore to the mill. The Grasberg gyratory crushers and conveyor system delivered ore to the top of four vertical ore passes and dropped the ore about 2,000 feet to ore bins below. The ore then was conveyed from the ore bins to the mill stockpiles.

The gravity associated with a fall like that carries a lot of energy, enough to break the crushed ore from the in-pit crushers into smaller fragments; essentially pre-conditioning the ore for the mill crushing and grinding circuit.

But, with the underground mines at or below the mill elevation, the potential energy associated with the drop in the Grasberg pit ore passes was lost and needed to be replaced, Banini said. Also, the material that comes out of the underground mines is blockier by virtue of the block caving mining method, he said. The bottom line is, compared with the open pit era, there are too many big rocks in the mix to send to the primary grinding process or to the secondary crushers if the same level of throughput is expected.

Replacing lost energy

That’s where the new SAG 3 mill comes in.

“We lost breakage energy when we moved underground because we lost the ore passes from Grasberg,” Banini said. “In order to mill the same optimal level of mine output, we need to replace that energy loss. That is what is drove SAG 3. It basically is a ‘replacement’ of the ore passes that also helps keep higher production levels during maintenance of one of the other SAG mills.”

“We lost breakage energy when we moved underground because we lost the ore passes from Grasberg,” Banini said. “In order to mill the same optimal level of mine output, we need to replace that energy loss. That is what is drove SAG 3. It basically is a ‘replacement’ of the ore passes that also helps keep higher production levels during maintenance of one of the other SAG mills.”

Unlike a conventional ball mill, which uses steel balls to break up the rocks, a SAG mill uses a mix of steel balls and the energy associated with the bigger rocks in the feed to break other particles into smaller fragments.

Newly mined ore is sent to mine crushers before the SAG mills. The discharge from the SAG mills is screened so undersize material is fed into ball mills for further processing while oversize material is either returned to the SAG mill or crushed in pebble crushers.

In the underground area, there are several other key pieces of infrastructure required to help ensure the mine and mill are operating at optimal levels and handling the increased copper concentrate production. These include:

A third GBC gyratory crusher that began operating in September designed to handle the kind of wet muck common from PTFI’s underground mining. It has the capacity to crush more than 60,000 tons of ore per day.

A third GBC gyratory crusher that began operating in September designed to handle the kind of wet muck common from PTFI’s underground mining. It has the capacity to crush more than 60,000 tons of ore per day. A new copper cleaner circuit to help maximize metal recovery while improving concentrate grade that is under construction and expected to be commissioned in August.

A new pressure filtration system at the dewatering plant constructed and commissioned in August to eliminate filtration as a bottleneck.

Also, to smelt and refine the Grasberg production, the new Manyar smelter has a nameplate capacity of 1.7 million tons of copper concentrate annually.

“It’s all interconnected” Banini said. “All of these building blocks are required for us to be able to continue to produce at optimal levels and to have in-country smelters to process 3 million tons of concentrate per year.”