The company’s last remaining mill that produced uranium for the national defense and energy needs of the United States is ready to be turned over to the federal government after decades of environmental cleanup and monitoring.

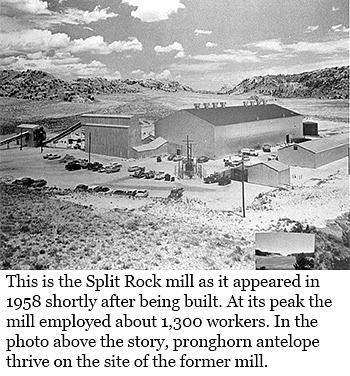

The Split Rock uranium mill, located near Jeffery City, Wyo., is a legacy property that produced uranium to supply both U.S. nuclear defense programs and the civilian power industry from 1957 until it was closed in 1981. The mill, the first in Wyoming, used a concentrate leach/solvent extraction process to recover uranium from locally produced ore, which then was sold as uranium concentrate commonly known as “yellow cake.” The facility originally was built by a company called Western Nuclear Inc., which processed about 7.7 million tons of uranium ore from nearby mines in central Wyoming during the height of the Cold War and the burgeoning age of nuclear power generation.

The Split Rock uranium mill, located near Jeffery City, Wyo., is a legacy property that produced uranium to supply both U.S. nuclear defense programs and the civilian power industry from 1957 until it was closed in 1981. The mill, the first in Wyoming, used a concentrate leach/solvent extraction process to recover uranium from locally produced ore, which then was sold as uranium concentrate commonly known as “yellow cake.” The facility originally was built by a company called Western Nuclear Inc., which processed about 7.7 million tons of uranium ore from nearby mines in central Wyoming during the height of the Cold War and the burgeoning age of nuclear power generation.

Western Nuclear was acquired by Phelps Dodge Corp. in 1971. Though Freeport never operated the mill, it assumed responsibility for mitigating any environmental issues and maintaining the property when it acquired Phelps Dodge in 2007. Site cleanup began in 1990 and was completed 15 years later. Since then, it has been monitored under strict regulatory supervision by both the Nuclear Regulatory Commission and the State of Wyoming to ensure there is no environmental risk.

The next step is for the federal government to take ownership of the mill property and about 5,400 surrounding acres under a law passed in 1978 to encourage uranium production, said Larry Corte, Senior Counsel I at Freeport-McMoRan and President of its WNI subsidiary. That will relieve Freeport of all future regulatory obligations and liabilities associated with the uranium mill.

“From the shareholders’ standpoint, it mitigates any residual long-term liability,” Corte said. “From a policy standpoint we’ve been good corporate stewards and fulfilled all of our radiological safety mitigation and tailings reclamation obligations with the Nuclear Regulatory Commission and the State of Wyoming.

“We’ve completed our final reclamation based on the strict engineering standards set forth by the Nuclear Regulatory Commission and the State of Wyoming which address both radiological safety and environmental impacts associated with uranium processing waste and tailings produced at the site going from the beginning of the plant back in the late 1950s, to completely remediating it in the early part of this century. This final outcome is a success story in terms of environmental stewardship.”

Strategic production

When the mill opened, both the strategic and economic demand for uranium were booming. It was vital for nuclear weapons development as the U.S. was locked in a global standoff with the Soviet Union. Nuclear power also was on the rise and seen as a cheap and reliable source of electricity.

At the time, there was little thought about the environmental consequences of uranium milling, processing and the resulting mill tailings. Consequently, there were almost no regulations such as requirements that tailings impoundments be lined to prevent infiltration into the groundwater.

By the late 1960s, there was growing awareness about the risks of uranium production and more concern about environmental protection. That led to the passage of the Uranium Mill Tailings Radiation Control Act of 1978, which imposed stringent regulations on uranium production, particularly on tailings and other milling waste.

As a tradeoff to new regulations, and a recognition uranium was critical to the national defense, the law created a mechanism allowing producers to turn ownership of decommissioned milling facilities over to the federal government to manage the former mill site as the permanent legal custodian. To do that, they would first need to fix any environmental issues and restore the site to a safe and stable condition. This legal process relieves the former mill owner – in this case, Freeport – of the obligation to maintain the properties, these obligations being transferred permanently to the federal government.

Initially, the Split Rock mill was so successful that it underwent multiple expansions to keep up with demand, depositing its tailings in unlined impoundments where wastes eventually seeped into the groundwater.

Boom goes bust

The good times ended suddenly in 1979, when an accident at the Three Mile Island nuclear reactor in Pennsylvania triggered a partial meltdown in what remains the most serious nuclear incident in U.S. history. That, coupled with a subsequent fictional movie, “The China Syndrome,” sent demand for uranium – and the price along with it – plummeting. The Split Rock mill continued operating, largely filling old contracts at the higher price, before closing permanently in 1981. Any plans to reopen the mill were abandoned in 1986.

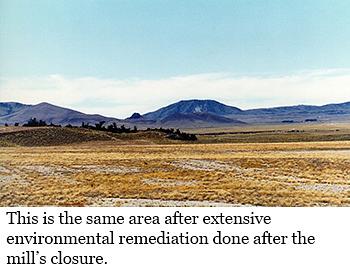

The mill was dismantled, and all unsalvageable equipment was buried on site. Remediation of contaminated groundwater began in 1990 and lasted for the next 16 years. Soil cleanup commenced in 1995 and took two years. The tailings were covered with layers of soil, rock and a radon barrier, creating a safe impoundment engineered to withstand erosion and remain stable for 1,000 years without maintenance.

The cost of the cleanup was about $70 million. The company has been reimbursed $31 million by the federal government under a law passed in 1992 that allows uranium producers to be repaid for remediation costs associated with filling orders from federal agencies. Federal contracts represent about 44 percent of the uranium produced at the site, and therefore, the company qualifies for reimbursement of 44 percent of its remediation costs.

The cost of the cleanup was about $70 million. The company has been reimbursed $31 million by the federal government under a law passed in 1992 that allows uranium producers to be repaid for remediation costs associated with filling orders from federal agencies. Federal contracts represent about 44 percent of the uranium produced at the site, and therefore, the company qualifies for reimbursement of 44 percent of its remediation costs.

So now, more than 40 years after the mill closed and 15 years after the cleanup work was completed, Western Nuclear has conveyed title to the property over to the U.S. Department of Energy, which now will assume all long-term maintenance obligations required to manage the site. This milestone marks the last major step in a lengthy regulatory process, Corte said. To close the deal, the company, in compliance with applicable federal regulations, has paid the U.S. Department of Energy a one-time “long-term care fee” of $4.2 million to cover expenses for future monitoring of the site.

With that, Western Nuclear will effectively cease to exist, and Freeport will be shed of its last uranium mill, having ceded one in Washington state to the federal government in 2001.

“We will no longer be obligated to maintain or take further remedial actions to rehabilitate the property,” Corte said. “We have fulfilled our commitment to reclaim the site in adherence to strict regulatory benchmarks. Our decades-long effort leaves behind a fully reclaimed mill site and adjacent tailings, and our dividend from sound environmental stewardship, a legacy operation now without future regulatory liability or ongoing obligations.”